Researches

Social Issues Research Centre: The Smell Report

Emotion

The perception of smell consists not only of the sensation of the odors themselves but of the experiences and emotions associated with these sensations. Smells can evoke strong emotional reactions. In surveys on reactions to odors, responses show that many of our olfactory likes and dislikes are based purely on emotional associations.

The association of fragrance and emotion is not an invention of poets or perfume-makers. Our olfactory receptors are directly connected to the limbic system, the most ancient and primitive part of the brain, which is thought to be the seat of emotion. Smell sensations are relayed to the cortex, where ‘cognitive’ recognition occurs, only after the deepest parts of our brains have been stimulated. Thus, by the time we correctly name a particular scent as, for example, ‘vanilla’, the scent has already activated the limbic system, triggering more deep-seated emotional responses.

Mood-effects

Although there is convincing evidence that pleasant fragrances can improve our mood and sense of well-being, some of these findings should be viewed with caution. Recent studies have shown that our expectations about an odor, rather than any direct effects of exposure to it, may sometimes be responsible for the mood and health benefits reported. In one experiment, researchers found that just telling subjects that a pleasant or unpleasant odor was being administered, which they might not be able to smell, altered their self-reports of mood and well-being. The mere mention of a positive odor reduced reports of symptoms related to poor health and increased reports of positive mood!

More reliable results have been obtained, however, from experiments using placebos (odorless sprays). These studies have demonstrated that although subjects do respond to some extent to odorless placebos which they think are fragrances, the effect of the real thing is significantly greater. The thought of pleasant fragrances may be enough to make us a bit more cheerful, but the actual smell can have dramatic effects in improving our mood and sense of well-being.

Although olfactory sensitivity generally declines with age, pleasant fragrances have been found to have positive effects on mood in all age groups.

In experiments involving stimulation of the left and right nostrils with pleasant and unpleasant fragrances, researchers have found differences in olfactory cortical neurons activity in the left and right hemispheres of the brain which correlate with the ‘pleasantness ratings’ of the odorants. These studies are claimed to indicate that positive emotions are predominantly processed by the left hemisphere of the brain, while negative emotions are more often processed by the right hemisphere. (The ‘pleasant’ odorant used in these experiments, as in many others, was vanillin.)

Perception effects

The positive emotional effects of pleasant fragrances also affect our perceptions of other people. In experiments, subjects exposed to pleasant fragrances tend to give higher ‘attractiveness ratings’ to people in photographs, although some recent studies have shown that these effects are only significant where there is some ambiguity in the pictures. If a person is clearly outstandingly beautiful, or extremely ugly, fragrance does not affect our judgement. But if the person is just ‘average’, a pleasant fragrance will tip the balance of our evaluation in his or her favour. So, the beautiful models used to advertise perfume probably have no need of it, but the rest of us ordinary mortals might well benefit from a spray or two of something pleasant. Beauty is in the nose of the beholder.

Unpleasant smells can also affect our perceptions and evaluations. In one study, the presence of an unpleasant odor led subjects not only to give lower ratings to photographed individuals, but also to judge paintings as less professional.

The mood-improving effects of pleasant smells may not always work to our advantage: by enhancing our positive perceptions and emotions, pleasant scents can cloud our judgement. In an experiment in a Las Vegas casino, the amount of money gambled in a slot machine increased by over 45% when the site was odorized with a pleasant aroma!

In another study – a consumer test of shampoos – a shampoo which participants ranked last on general performance in an initial test, was ranked first in a second test after its fragrance had been altered. In the second test, participants said that the shampoo was easier to rinse out, foamed better and left the hair more glossy. Only the fragrance had been changed.

Scent-preferences

Scent-preferences are often a highly personal matter, to do with specific memories and associations. In one survey, for example, responses to the question ‘What are your favorite smells?’ included many odors generally regarded as unpleasant (such as gasoline and body perspiration), while some scents usually perceived as pleasant (such as flowers) were violently disliked by certain respondents. These preferences were explained by good and bad experiences associated with particular scents. Despite these individual peculiarities, we can make some significant generalizations about smell-preference. For example, experiments have shown that we tend to ‘like what we know’: people give higher pleasantness ratings to smells which they are able to identify correctly. There are also some fragrances which appear to be universally perceived as ‘pleasant’ – such as vanilla, an increasingly popular ingredient in perfumes which has long been a standard ‘pleasant odor’ in psychological experiments (see Vanilla).

A note for perfume-marketers: one of the studies showing our tendency to prefer scents that we can identify correctly also showed that the use of an appropriate color can help us to make the correct identification, thus increasing our liking for the fragrance. The scent of cherries, for example, was accurately identified more often when presented along with the color red – and subjects’ ability to identify the scent significantly enhanced their rating of its pleasantness.

Doctor Aromas and the benefits of Scent Marketing

It is necessary to be creative when you are trying to win or retain clients, also to increase productivity or to improve the conditions of your business.

From appealing to the sense of sight, in the form of an attractive design, making use of the hearing with environmental music to using fragrances to appeal to the strongest sense: smell.

Smells can directly affect our behavior and body functions.

They can make us feel relaxed, calm, stimulated, provocative or seductive.

Based on studies in this field, the impact of olfactory stimulation in outlet centers was assessed, and it was observed that, when customers capture a nice smell, they evaluate better the environment and the products, spend more, intend to return more often to the business, and stay longer at the same place, because they value time as shortest than experienced.

Consequently, workplaces will become more pleasant, and the quality of spaces and productivity will raise up.

Different international companies currently use scent marketing and ensure that their sales increased since they aromatized their premises.

The same concept is verified in workplaces.

The introduction of a fragrance builds up attention and concentration, reduces stress, fatigue and anxiety, increasing the effectiveness of employees.

The use of scent marketing, in addition to create a surprise effect and being a differentiation factor, induces a better impression of the name with which it is associated.

It reinforces and complements the image of a brand or establishment, beyond the product or service they offer.

In short, it generates a friendly and favorable customers-answer when it comes to purchase, close a deal and/or pay the service or product offered.

In this sense, scent marketing relates a concept of product or establishment to a specific fragrance.

Neuromarketing: Why you need a Scent Logo | by Jennifer Dublino

All marketers are familiar with the concept of a logo, a visual representation of a brand. Some, like Coca Cola, Disney, Apple and Nike are so iconic that exposure to them, even when they aren’t noticed, affects our behavior.

For these large companies with their massive marketing budgets, it is fairly easy to expose large numbers of people to their logo and brand identity.

As a result, their brand recall is close to 100% throughout a good part of the world.

But what about small and medium-sized companies?

The average person is exposed to up to 5,000 ads a day.

How can you get customers to remember your brand with all this clutter?

The surprising answer is through the sense of smell.

The sense of smell is the only one of our five senses that is directly connected to the part of the brain that processes emotion, memory and associated learning.

In fact, you are 100 times more likely to remember something that you smell than something that you see, hear or touch.

Savvy marketers utilize this fact by creating an olfactory logo for their business.

An olfactory logo, also called scent branding, is a custom scent that the brand creates to embody its unique brand characteristics.

Much like a graphic logo, the olfactory logo is used wherever the brand is present.

After repeated exposures to the olfactory logo, the smell becomes strongly associated with that brand.

In order to work, the signature scent needs to be consistent with the image and emotions of the brand.

Think about the personality of your brand.

Is your brand reliable and trustworthy or edgy and fun?

Is your brand relaxed or power charged?

Also think about your target market.

Are they young, middle-aged or older?

Predominantly male or female?

Value or luxury buyers?

These characteristics can be successfully matched with different fragrance elements to create a scent that embodies your brand characteristics.

A highly successful use of scent branding is Abercrombie & Fitch.

Their signature fragrance, Fierce, is dispersed in high concentrations in all of their stores.

Fierce is strong, edgy and appeals to young, upscale consumers.

The result?

Fierce (which is also sold as a personal fragrance) is the number one selling fragrance for men in the US and Europe and A&F’s teenage and young adult target market can easily identify authentic A&F jeans solely by their smell.

Most of the major hotel chains also use an olfactory logo.

For example, the Westin uses a cool and relaxing white tea fragrance, and the St. Regis uses an elegant blend of rose, sweet pea and pipe tobacco.

Once you have created your signature scent, use it in every possible customer touchpoint, so that it can become associated closely with your brand in the customer’s mind.

If you have a hotel, store, spa or other location for your business, you can use a scent diffuser to disperse the fragrance in the air.

Companies producing packaged goods can incorporate the scent into their packaging.

Then, to spur repeat sales, use the scent in direct mail to remind customers of their positive experience with your brand.

Before you know it, your brand will be top of mind, and the aroma you detect will be the sweet smell of success!

Rockefeller University: How Scent Marketing Could Drive You Results

Since July 1st 1941 when Bulova (the watchmaker) paid $9 for a placement during a baseball game to be broadcasted in NY, we have gone to the TV as the most important marketing aid discovered.

Even today, during the ‘digital era’ where Facebook accounts for 600+ million users, YouTube monetizes more than 2 Billion videos per week, and more video is uploaded in 60 days than the networks did in 60 years (more in this amazing infographic), and so on, internet still is the 2nd most important source of communication (after TV – According to TVB Media Comparison Study 2010)

All the major consumer media (TV, Internet, Radio, Newspapers) are based on a sense (or a combination of them) that is not very potent.

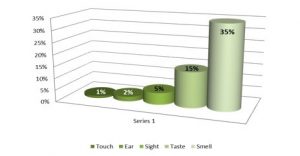

According to a Rockefeller University study, the reminiscent “power” of each of our senses is as follows:

- Touch ( 1%)

- Ear ( 2%)

- Sight ( 5%)

- Taste (15%) – 80% of which is smell

- Smell (35%)

And still we keep focusing on the least powerful senses to acquire consumers.

Scent Marketing could drive your brand (sales) results because it uses the most powerful sense the human body has.

Have you ever notices how this products are remembered by the costumers as for their great scent:

- Baby Shampoo by Johnson & Johnson

- The newness of a dealership car

- Most Hospitals Cleanliness

- A Bakery’s recent bread – Has worked great for large supermarkets in-store bakeries.

- The smell of chocolate in a confectionery shop

- Old books in a Library

There are other studies that support that scent strengthens consumer loyalty and perceptions of quality.

And fragrances evoke moods and enhance brand recall.

Obvious candidates for scent marketing are hotels, transportation providers, retail stores, etc. who too often ignore the possibilities of olfactory marketing.

Perhaps you should go to a Sony Style Store and sniff… this is no ordinary stuff, this is science!!

This is scent marketing!!

Or notice on your next trip to a Bloomingdale’s that the infant department smells like baby powder, the intimate apparel has scent of lilac or the swimsuit department to coconut (this could work for a travel agency in summer).

If you’re up for the challenge, keep in mind these examples on how to make scent work for your brand or business:

- Use a signature scent to define a brand

- Use scent to put consumers at ease

- Use scent to define spaces, or zones

University of St. Gallen: Just follow your nose

Customers’ buying mood is enhanced by agreeable scents in a shop. Scientists of the Center for Customer Insight at the University of St.Gallen (FCI-HSG) have provided evidence of this.

Many products and product ranges in shops barely differ from each other. This is why marketing specialists work with light, color, music and images in order to increase customers’ buying mood and accentuate individual products.

Direct impact on the emotional center

Yet no sensory input is processed more quickly in the brain than scent, since it impacts directly on the emotional center and thus on the oldest part of the brain. If a scent is as simple as possible and matches a product, it will facilitate the purchasing decision.

Sales slips as proof

The FCI-HSG’s scientists did not merely content themselves with trials under laboratory conditions to provide evidence of this effect. Rather, they had more than a thousand customers in four shops observed for weeks. Only sales slips were accepted as proof of how much a customer had spent.

The result was unequivocal: the right scent led to a turnover increase of 3 to 8 percentage points depending on the product and the shop. It enhances people’s sense of well-being and thus their buying mood – and it becomes even more important than information about price or quality.

Washington State University: Smells like Christmas spirit

Scientists and business people have known for decades that certain scents—pine boughs at Christmas, baked cookies in a house for sale—can get customers in the buying spirit. Eric Spangenberg, a pioneer in the field and dean of the Washington State University College of Business, has been homing in on just what makes the most commercially inspiring odor.

Spangenberg and colleagues at WSU and in Switzerland recently found that a simple scent works best.

Writing in the Journal of Retailing, the researchers describe exposing hundreds of Swiss shoppers to simple and complex scents. Cash register receipts and in-store interviews revealed a significant bump in sales when the uncomplicated scent was in the air.

“What we showed was that the simple scent was more effective,” says Spangenberg.

The researchers say the scent is more easily processed, freeing the customer’s mind to focus on shopping. But when that “bandwidth” is unavailable customers don’t perform cognitive tasks as effectively, says Spangenberg.

Working with Andreas Herrmann at Switzerland’s University of St. Gallen, Spangenberg, marketing professor David Sprott and marketing doctoral candidate Manja Zidansek developed two scents: a simple orange scent and a more complicated orange-basil blended with green tea. Over 18 weekdays, the researchers watched more than 400 customers in a St. Gallen home decorations store as the air held the simple scent, the complex scent or no particular scent at all.

The researchers noticed that one group of about 100 people on average spent 20 percent more money, buying more items. They had shopped in the presence of the simple scent.

In a series of separate experiments, WSU researchers had undergraduate students solve word problems under the different scent conditions. They found participants solved more problems and, in less time, when the simple scent was in the air than with the complicated one or no scent at all. The simple scent, say the researchers, contributed to “processing fluency,” the ease with which one can cognitively process an olfactory cue.

The research, says Spangenberg, underscores the need to understand how a scent is affecting customers. Just because pine boughs or baked cookies smell good doesn’t mean they will lead to sales.

“Most people are processing it at an unconscious level, but it is impacting them,” says Spangenberg. “The important thing from the retailer’s perspective and the marketer’s perspective is that a pleasant scent isn’t necessarily an effective scent.”